Congenital Heart Disease: Cases

Congenital Heart Disease: Cases

Pediatric Emergency Playbook

pemplaybook.org

info_outline Congenital Heart Disease: Plumbing & Air for the Emergency Physician

Congenital Heart Disease: Plumbing & Air for the Emergency Physician

Pediatric Emergency Playbook

pemplaybook.org

info_outline Precipitous Delivery

Precipitous Delivery

Pediatric Emergency Playbook

info_outline From the Ashes of SIRS: The Phoenix Sepsis Score

From the Ashes of SIRS: The Phoenix Sepsis Score

Pediatric Emergency Playbook

pemplaybook.org

info_outline Torticollis

Torticollis

Pediatric Emergency Playbook

www.PEMplaybook.org

info_outline Resuscitative Umbilical Vein Catheterization

Resuscitative Umbilical Vein Catheterization

Pediatric Emergency Playbook

pemplaybook.org

info_outline Update 2023

Update 2023

Pediatric Emergency Playbook

pemplaybook.org

info_outline Neonatal Resuscitation

Neonatal Resuscitation

Pediatric Emergency Playbook

pemplaybook.org

info_outline Stridor, Stertor, and Noisy Breathing

Stridor, Stertor, and Noisy Breathing

Pediatric Emergency Playbook

PEMplaybook.org

info_outline Brief, Huddle, and Debrief in the PED

Brief, Huddle, and Debrief in the PED

Pediatric Emergency Playbook

info_outline

"She won't walk", or "He just looks like he's limping".

So many things can be going on -- how do we tackle this chief complaint?

You’re dreading a big work-up. You almost want to tell the kid – please, STOP LIMPING...

STOP LIMPING!

S – Septic Arthritis

The most urgent part of our differential diagnosis. The hip is the most common joint affected, followed by the knee. Lab work can be helpful, as well as US of the hip to look for an effusion, but sometimes, regardless of the results, the joint just has to be tapped to know for sure.

T – Toddler’s fracture

This is usually a torque injury when the wobbling toddler pivots quickly or trips and falls. Toddler’s fractures happen in children 1 to 3 years of age, and occur in the distal 1/3 of the tibia. Sometimes a cast is needed, but currently there is a new trend in foregoing casting in mild cases.

O – Osteomyelitis

Bacteremia – from any source – can seed into any bone. It’s not very common, but it happens: approximately 2% of children who present to an ED with limp will have osteomyelitis. Plain films, ESR, and CRP are a fair screen to start. For more than the casual concern, MRI is the best modality to evaluate, followed by radionuclide scintigraphy. Although not the first choice modality, CT can show periosteal changes, such as inflammatory new bone formation or periosteal purulence.

P – Perthes disease

This is the famous Legg-Calvé-Perthes idiopathic avascular necrosis of the hip, usually affecting children from 3 to 12 years. They present with a slow onset pain and with an antalgic gait. Patients will have trouble with internal rotation and abduction of the hip. Radiographs may be initially normal. MRI can show the culprit: decreased perfusion to the femoral head and subsequent necrosis.

L – Limb-Length Discrepancy

Parents may notice that he seems “wobblier” than he should be. It may be that we are just now appreciating a congenital anomaly. Get out the paper tape, and measure from the anterior superior iliac spine to the medial malleolus and compare both sides. Children with limb-length discrepancy only need a non-urgent referral to pediatric orthopedics to look for congenital dysplasia of the hip, or other growth abnormalities. Some are treated with orthotics. Surgical options vary. Epiphysiodesis destroys the growth plate on the unaffected side, which evens out the growth. Other options are limb-lengthening or limb-shortening procedures.

I – Inflammatory

Transient Synovitis. This is what we want them to have right? The typical age is between 3 and 6 years, sometimes just after a URI. To be comfortable with this diagnosis, we should have considered all of the dangerous diagnoses, the child should be well, afebrile, in minimal discomfort, and he should respond almost completely to an NSAID. He’s the one running up and down the department after treatment – or just from sheer boredom after observation.

M – Malignancy

Primary bone tumors such as Ewing’s sarcoma or osteogenic sarcoma typically affect older children. Limping, however, may be a presenting symptom of leukemia. If you have any suspicion of the general wellness of the child, get a screening CBC, and perhaps a peripheral blood smear. Whatever you do, make sure you get close follow up for these kids that are on your malignancy radar -- the blast crisis may not have occurred yet – but it can happen hours to days later.

Plain films are insensitive for leukemic involvement of bone but they may show diffuse osteopenia, or metaphyseal bands – symmetrical high-uptake markings around the joint. They look like stacks of paper within normal bone – you can see them also in anemia, lead poisoning, and other causes. Also look for periosteal new bone formation, sclerosis, or lysis.

P – Pyomyositis

This usually presents with vague irritability, pain, and fever, and sometimes with a subacute minor trauma. These children don’t look to well.

Also think about just run-of-the-mill myositis, usually from a viral cause, such as influenza. Typically the calves are affected and are always tender. Hydration and supportive therapy are indicated for viral causes.

For bacterial focal pyomyositis, give empiric antibiotics, admit them for major inpatient workup, and think about early surgical consultation if you think you need sepsis source control.

I – Iliopsoas Abscess

Children most often will develop a primary abscess from bacteremia from an unresolved infection. Adults more commonly form secondary abscesses from Crohn’s disease, post-op complications, a vertebral infection, or even a bad chronic urinary tract infection. Lest you think this is a dramatic presentation, think again: iliopsoas abscesses present also with vague symptoms of back, flank, abdominal, or hip pain, sometimes with fever. The median time from symptoms to diagnosis in children is a whopping 20+ days, according to one study. If iliopsoas abscess is starting to get your attention, get the CT or MRI.

N – Neurologic

Not to scare you, but children do have strokes; unlike adults, half are hemorrhagic, half are thromboembolic. Typically they’ll have some underlying pathology that will alert you, such as a cardiac lesion, sickle cell disease, or some infectious or metabolic history. The good news is that it won’t just be a limp – you’ll have some other neuro sign or symptom to go after.

Guillain Barré is another thing to consider – early lower extremity weakness may present as a limp or refusal to walk. Maybe it’s not the hip that should be tapped, but the spinal canal.

Think also about muscular dystrophy or peripheral neuropathy and its possible underlying etiology.

G – Gastrointestinal and Genitourinary

What else could be going on? Appendicitis may be faking you out here. Perhaps there is a hernia, or testicular or ovarian torsion, all of which can present as lateralizing pain and not wanting to walk. Think outside the box.

Phases of Gait

The gait cycle has three phases: contact, stance, and propulsion. Contact is the time from heel strike to just when the foot is flat. Stance is from the foot being flat to lifting the heel from the ground. The stance phase is when you bear most of your weight. The propulsion phase is when your weight transfers to your toes, and you push off.

Abnormal Gaits

Antalgic Gait -- "hobbling" gait; normal contact phase, but stance phase is abbreviated; propulsion is normal. The patient is trying to limit the time spent bearing weight on that side.

Trendelenburg Gait -- the affected side's hip abductor muscles are too weak or painful to stabilize the pelvis; the unaffected side dips to the floor. May be superior gluteal neuropathy, or a biomechanical problem, such as avascular necrosis, congenital dysplasia of the hip, or slipped capital femoral epiphysis.

Circumduction Gait -- the patient swings his foot laterally (due to a foot or ankle pathology), or to avoid tripping in limb-length discepancy.

Stiff-leggged Gait -- the patient walks with knees locked, in an attempt to avoid using the gastrocnemius muscles; concerning for myositis.

Equinus Gait -- toe-walking, as seen in myositis, also to avoid exacerbating pain from the calves.

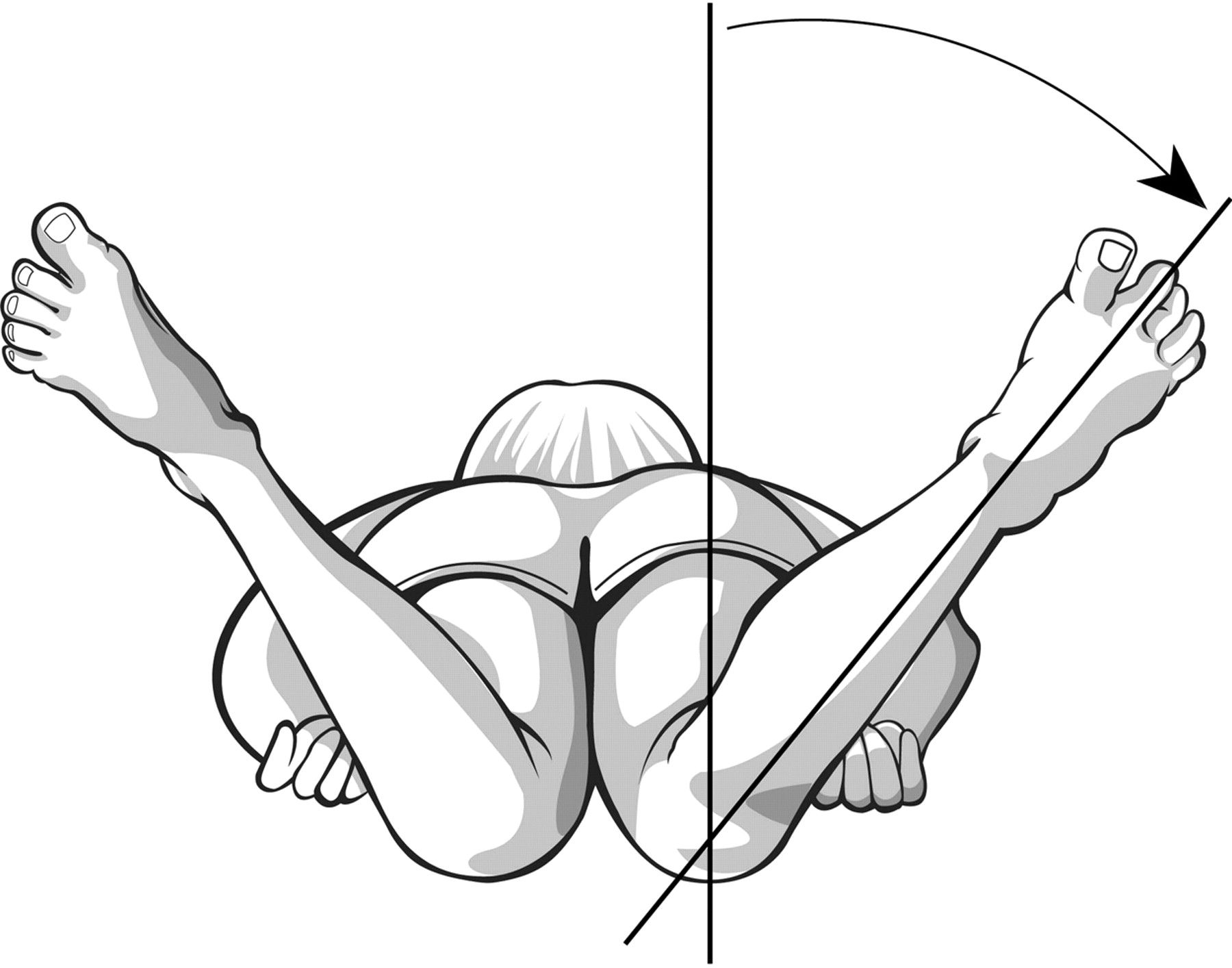

Lag of Internal Rotation of the Hip

Lag of Internal Rotation of the Hip

Look for symmetry of internal rotation, or lateralizing pain or "guarding" with range of motion.

Keep the pelvis flush to the bed, and simultaneously rotate the lower extremity laterally, which will cause internal rotation of the hip.

Avascular necrosis will not allow full internal rotation, since the joint space is narrowed with this maneuver, causing impingement of the sensitive necrotic head of the femur.

Note any pain, asymmetry, and angle of internal rotation achieved.

Kocher Criteria

In their original paper in 1999, Dr Kocher et al. performed a retrospective analysis of children who were being evaluated for a septic joint versus transient synovitis over a 15 year period, in a major referral center. They came up with four independent predictors of a septic joint, and calculated the probability of septic arthritis based on the number of features present. In 2004 the same group validated their prediction tool, with a slightly decreased sensitivity and specificity in the validation population.

In short, the Kocher criteria are not perfect, but it’s the best evidence we have at the moment.

The four predictors are:

Inability to walk

Fever of 38.5 C of greater

ESR > 40 mm/h

WBC > 12,000

Bonus mnemonic: Walk FEW: Inability to Walk | Fever | ESR | WBC

The probability of septic arthritis increases with increasing predictor. In this prediction model, each predictor has the same weight.

Probability of Septic Arthritis (Kocher et al. 1999)

0 Predictor – <0.2 %

1 Predictor – 3%

2 Predictors – 40%

3 Predictors – 93.1%

4 Predictors – 99.6%

Now, remember, this is to be used in children in whom you already have some suspicion of a septic joint. So, 0 predictors, generally you’re alright. 1 predictor, you may start to worry. Once you have 2 predictors, your chances jump for 3% to 40%. You really have to go looking.

The Kocher caveat is that there is no single test or single decision rule that will stop you from investigating if you are concerned enough. Don’t have too much faith in this imperfect decision tool – we use it because we need somewhere to start. Treat and push for the aspiration of the hip if you are left in doubt. Septic arthritis can be devastating if not identified early.

Summary

- Fever and limp? – do not pass go – especially with 2 or more Kocher criteria – or if there is any doubt, tap that joint.

- Refusal to walk after adequate analgesia? Admit for observation, MRI, further workup, blood cultures, and much more.

- Remember some developmental concerns to help you to decide whether to continue the investigation urgently as an inpatient, or non-urgently as an outpatient.

- After all of that, try to get them them to STOP LIMPING!

References

Lindsay D, D'Souza S. A limping child. BMJ. 2016 Feb 9;352:i476.

Verma S. Pyomyositis in Children. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2016 Mar;18(4):12.

This post and podcast are dedicated to the estimable yet graciously humble Andrew Tagg BSC(Hons), MBBS, MRCSEd, ACEM for his dedication to #FOAMed, Emergency Medicine, Pediatric Emergency Medicine, and all things caffeinated. Thank you for your dedication, generosity, and your example.

Don't Forget the Conference! #DFTB17 #DFTB